John Schrank was born in Bavaria on March 5, 1876, and emigrated to the United States when he was 9. Things didn’t go all that well for John. His parents died soon after their arrival. He was taken in by an aunt and uncle, working for them in their New York tavern. They also died, and when his only girlfriends died as well, he sold off his inheritance properties and set to rambling around the east coast. Just as this was beginning to sound like the plot of an opera, he got religion and became a bit of a biblical authority (at least in his own eyes), lecturing other folks on their sins in various barrooms and public places. Although he annoyed a lot of people, he did no real harm.

During the 1912 presidential contests, the Republican party suffered a schism, each side wanting the Republican tent to be a little smaller, excluding the other side. Conservatives were led by William Howard Taft, and moderates (known today as RINOs) were led by ex-President Theodore Roosevelt. When Taft won the nomination, Roosevelt bolted and formed the Bull Moose Party. Roosevelt was campaigning in Wisconsin when he was shot by our biblical scholar John Schrank. The bullet hit the text of Roosevelt’s speech, eliminating several dozen useless adjectives and other excess verbiage.

The speech was much improved and Roosevelt himself was unhurt. Schrank explained to authorities that he had nothing against Roosevelt as an individual; in fact he rather liked him. His quarrel was with ‘Roosevelt, the third-termer’ and was meant as a warning to any other politician who might seek a third term. And not only that, shooting Roosevelt was not his own idea. The ghost of William McKinley made him do it. The ghost rose up right out of a coffin, pointed at a picture of Roosevelt and said: “Do it.”

Even with this quite splendid explanation, the authorities nonetheless sent Schrank away to a Wisconsin mental hospital where he remained until his death in 1943.

Makes the Heart Grow Fonder

Although the United States threw in the towel on the prohibition of alcohol back in 1933, one alcoholic beverage remained in the crosshairs of the temperance types for another seven decades.

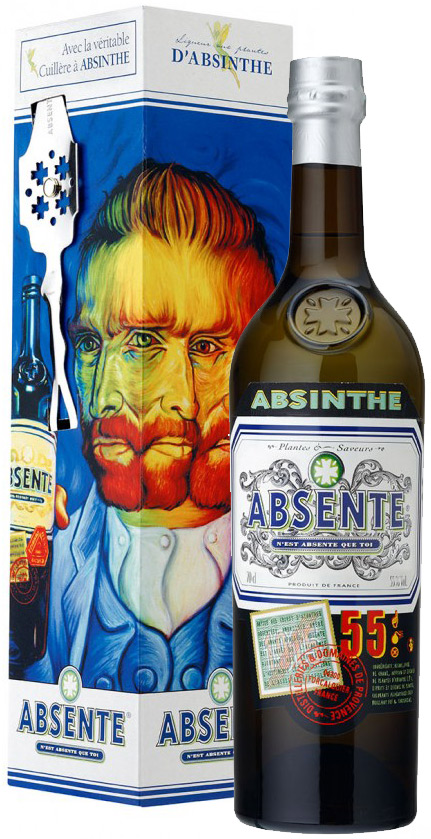

Absinthe, also known as the Green Fairy or the Green Lady, was created back in the early 19th century by French doctor, Pierre Ordinaire, an innocent enough sounding gentleman. It was made by infusing wormwood, fennel, anise and other herbs into alcohol, creating an elixir that tastes like licorice but packs a much more powerful punch. The good doctor used it to treat a variety of illnesses.

Absinthe, also known as the Green Fairy or the Green Lady, was created back in the early 19th century by French doctor, Pierre Ordinaire, an innocent enough sounding gentleman. It was made by infusing wormwood, fennel, anise and other herbs into alcohol, creating an elixir that tastes like licorice but packs a much more powerful punch. The good doctor used it to treat a variety of illnesses.

It later became trendy as an alcoholic beverage thanks to celebrity imbibers such as Ernest Hemingway, Pablo Picasso, Oscar Wilde, James Joyce and Vincent van Gogh, who thought it increased their creativity. But then came studies that unfairly claimed that absinthe not only had hallucinogenic effects but caused immorality, antisocial behavior and madness. Some critics even claimed that it was absinthe that led van Gogh to take a knife to his ear.

Absinthe was soon proscribed (as opposed to prescribed) pretty much everywhere, and remained so throughout the 20th century, until a host of modern studies cleared its name. It received its U.S. reprieve on March 5, 2007.