Those folks who think they have it pretty rough in Virginia these days should thank their reactionary stars things are not as they were back in 1619. The very first general assembly got together in Jamestown that year to pass laws that pretty much told everyone how they could and could not behave. The burgesses, as members of the assembly were called, were 30 old white men determined to dictate morality to everybody else, a tradition that hasn’t changed much over the years.

Nor has the politics. The burgesses passed laws requiring all colonists to attend two religious services every Sunday and to bear arms (pieces, swords, powder and shot) while doing so – just in case religious fervor pushed someone over the edge. Even those bearing arms were forbidden from gambling, drinking, idleness and “excesses in apparel,” (which probably didn’t mean too much clothing). Not wishing to overlook any sin they hadn’t thought of, the burgesses also approved a stern enactment against immorality in general. In the eyes of the burgesses, one can imagine, that might cover a lot of territory (and the colonies had lots of territory). The planting of mulberry trees, grapes and hemp was also proscribed, for we all know that that seemingly innocuous flora is the first step on the road to degradation (spelled with a ‘d’ and that rhymes with ‘p’).

The burgesses had only nice things to say about tobacco however. Colonists were urged to dedicate the times they were not in church to the growing of said crop. The colonists responded with enthusiasm, even to the point of growing tobacco in the streets of Jamestown – 20,000 pounds a year – despite His Royal Stick in the Mud King James calling it “dangerous to the lungs.”

♥

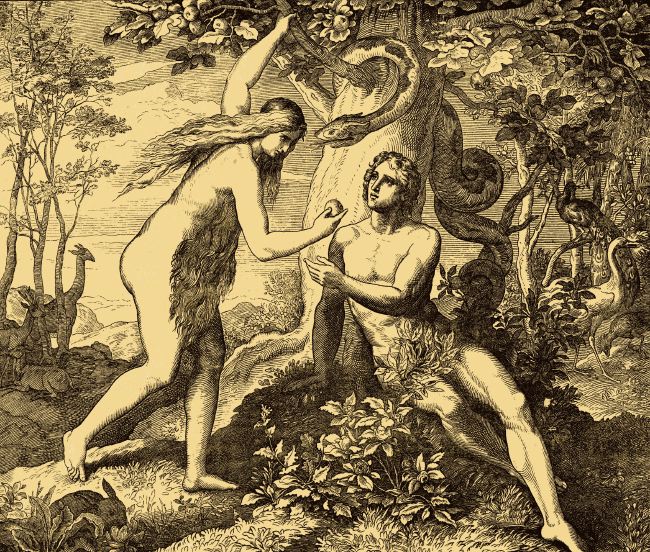

“Adam was but human—this explains it all. He did not want the apple for the apple’s sake, he wanted it only because it was forbidden. The mistake was in not forbidding the serpent; then he would have eaten the serpent.” ― Mark Twain