STAGECOACH POETICA

The California Gold Rush was in full swing by the latter half of the 19th century. Stagecoaches and Wells Fargo wagons were hauling gold out of California by the, well by the wagonload. All this gold was just too much of a temptation for some folks, transplanted New Yorker Charles Boles being one such tempted soul.

In the summer of 1875, Boles donned a white linen duster, put a flour sack over his head and a black derby on top of that and set about robbing the gold from a stagecoach leaving the mining city of Copperopolis. Boles stepped out in front of the stage, aimed a shotgun at the driver, forcing him to stop and demanding him to “Throw down the box.” The driver was reluctant to comply until he saw several gun barrels aimed at them from nearby bushes. He calculated the odds, and turned over the strongbox. Boles whacked the strongbox with an ax until it disgorged its treasure, which Boles hauled off while the stagecoach driver remained a captive of Boles’ fellow conspirators. After this standoff had lasted a bit too long, he moved to retrieve the empty strongbox and found that the rifles pointing at him were nothing but sticks tied to branches of the bushes.

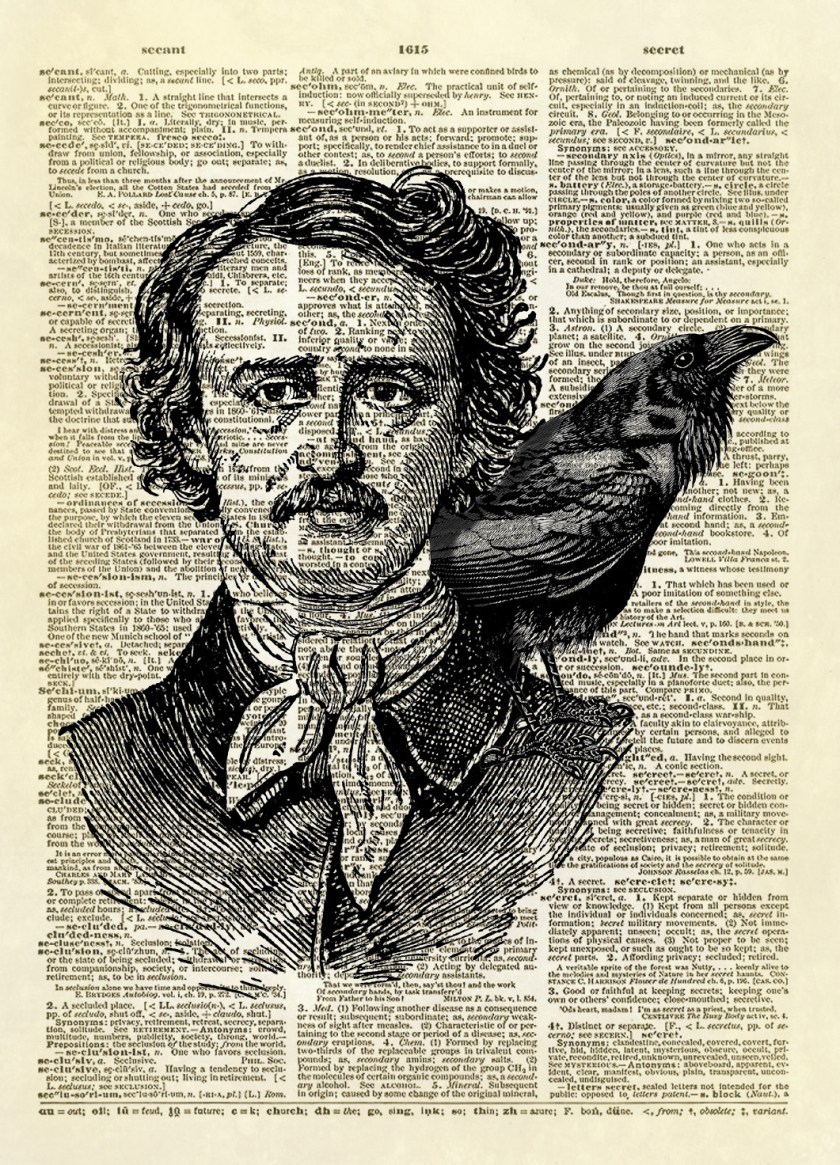

Boles was rather amazed at how easy this robbery business was and so, adopting the moniker Black Bart, he embarked on a life of crime. He became a bit of a legend due to his daring, the fact that he never rode a horse and leaving bits of verse “po8try” behind at each robbery:

I’ve labored long and hard for bread —

For honor and for riches —

But on my corns too long you’ve tred,

You fine-haired sons of bitches.

His victims also called him a gentleman. Once after ordering a stage drive to throw down the box, a frightened passenger tossed him her purse. Bart returned it to her, saying that he wanted only the strongbox and the mailbag.

Black Bart the Po8 robbed his last stagecoach on November 3, 1883 — that is, attempted to rob his last stage. Wells Fargo, not amused at having lost close to half a million to bandits, had secreted an extra guard on the stage. Bart escaped the trap but dropped his derby and left several other incriminating items behind a nearby rock. Within days, Black Bart had been apprehended.

During his eight years as a highwayman, Black Bart never shot anyone, nor did he ever rob an individual passenger. He stole a grand total of $18,000. Sentenced to six years in prison, he served four before receiving a pardon and disappearing into retirement.