Republicans were on the political attack and the President was angry. At a campaign dinner with the Teamsters union, on this day in 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt struck back. It was one thing for the Republicans to spread “malicious falsehoods” about him and Eleanor, but they had stepped over the line, making libelous statements about Fala, his small, black Scottish terrier.

After addressing weighty labor and war issues, Roosevelt blasted Republican critics for circulating a claim that he had accidentally left Fala behind while visiting the Aleutian Islands earlier that year and had, at a taxpayer cost of $20 million, sent a Navy destroyer to pick up the dog. Although Fala slept at the foot of President’s bed and received a bone every morning with Roosevelt’s breakfast tray, Roosevelt accused his critics of attempting to tarnish a defenseless dog’s reputation just to distract Americans from more pressing issues facing the country.

Did Richard Nixon, eight years later to the day, take a page out of the Roosevelt playbook to defend his own honor when critics accused him of accepting improper gifts and making funny with campaign funds? The story broke two months after Nixon’s selection as Dwight D. Eisenhower’s running mate, threatening Nixon’s place on the ticket. Nixon interrupted a whistle-stop tour of the West Coast to fly to Los Angeles for a television and radio broadcast to the nation in which he vowed he would not return one gift: a black-and-white dog who had been named Checkers by his children. But unlike Roosevelt, who took Fala to meetings with heads of state such as Winston Churchill, there is no evidence that Nixon even touched Checkers, let alone fed him.

Just Put Your Lips Together

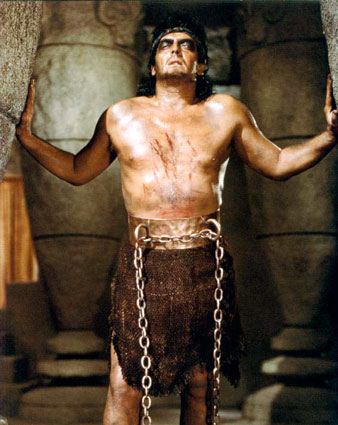

Harry “Steve” Morgan and his alcoholic sidekick, Eddie, are a couple of ne’er-do-wells crewing a boat for hire on the island of Martinique.  Life is okay, but World War II is happening all around them, doing a number on the tourist trade and thus their livelihood. Howard Hawks’ film To Have and Have Not which premiered in New York on October 11, 1944, was notable for bringing together what would become one of Hollywood’s hottest couples, Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall.

Life is okay, but World War II is happening all around them, doing a number on the tourist trade and thus their livelihood. Howard Hawks’ film To Have and Have Not which premiered in New York on October 11, 1944, was notable for bringing together what would become one of Hollywood’s hottest couples, Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall.

The film takes the title from the book by Ernest Hemingway but not much else. Hawks was a Hemingway fan but thought this particular book was a “bunch of junk.” Even so, Hemingway worked with Hawks on the screenplay, in which Bogart once again gives up his professed neutrality in the war to thwart the Nazis. The plot is well thickened by the stormy relationship between Bogart and Bacall who plays Slim, a saucy singer in the club where Morgan drinks away his days.

Another notable member of the cast is Hoagy Charmichael who appears as the club piano player, Cricket. He and Bacall perform several Charmichael songs: “How Little We Know,” “Hong Kong Blues,” and “The Rhumba Jumps.” Bacall does her own singing, even though persistent rumors would have a 14-year-old Andy Williams singing for her.

The most memorable take away from the film is one line of dialogue delivered seductively by Bacall: “You know how to whistle, don’t you, Steve? You just put your lips together and . . . blow . . .”

That’s what Paul might have yelled as she waddled (being a duck) off into the crowd of human-sized ducks and dogs and chipmunks at Disney World. He didn’t, but she came back anyway, and together they set off on a romantic adventure, facing an abundance of perils — neither of them toting a gun. Feel free to join them.

That’s what Paul might have yelled as she waddled (being a duck) off into the crowd of human-sized ducks and dogs and chipmunks at Disney World. He didn’t, but she came back anyway, and together they set off on a romantic adventure, facing an abundance of perils — neither of them toting a gun. Feel free to join them.