Do mermaids exist? These creatures – half woman, half fish – have found their way into the lore of seafaring cultures at least as far back as ancient Greece. You’ve seen  them depicted; a woman’s head and torso and the tail of a fish instead of legs. They’re most often quite attractive, gazing upon their own countenance in a mirror and combing their long flowing tresses (like Darryl Hannah in the movie Splash, for example).

them depicted; a woman’s head and torso and the tail of a fish instead of legs. They’re most often quite attractive, gazing upon their own countenance in a mirror and combing their long flowing tresses (like Darryl Hannah in the movie Splash, for example).

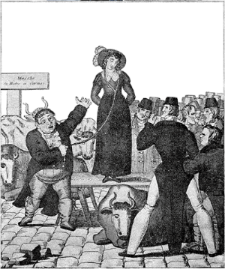

But believe in them? One might just as well believe in sirens, the half-woman, half-bird creatures who dwell on islands from where they sing seductive songs to lure sailors to their deaths. Yet there have been some notable sightings. No one less than Italian explorer Christopher Columbus has written of an encounter. On January 9, 1493, the intrepid New World traveler spotted not one but three mermaids frolicking somewhere near the Nina, Pinta or the Santa Maria (or maybe one entertaining each ship?)

He described the sighting in his ship’s journal: “They were not as beautiful as they are painted, although to some extent they have a human appearance in the face.” Columbus’ account would give ammunition to conspiracy theorists who claim that most mermaid sightings are actually manatees — sea cows, although they’re said to share a common ancestor with elephants. Manatees are slow-moving aquatic beasts, weighing a good thousand pounds with bulbous faces but Bette Davis eyes. Most moviegoers would not mistake them for Darryl Hannah.

Henry Hudson, a British and therefore more reliable explorer, also sighted a mermaid “come close to the ship’s side, looking earnestly on the men. A little while after, a sea came and over-turned her. From the navel upward her back and breast were like a woman’s . . .her body as big as one of ours; her skin very white, and long hair hanging down behind . . . In her going down they saw her tail, which was like the tail of a porpoise, and speckled like a mackerel.” Much better, except for the mackerel part.

A few years later, Captain John Smith, of Pocahontas fame, spotted a mermaid off the coast of Massachusetts. He wrote that the upper part of her body perfectly resembled that of a woman and that she swam about with style and grace. She had “large eyes,

rather too round, a finely shaped nose (a little too short), well-formed ears, rather too long. . .” And she probably thought Smith was a little too much of a jerk.

Naturally, there is a male counterpart for the mermaid: the merman. Collectively we might call them merfolk.

The most famous of the mermen was the Greek god Triton, the messenger of the sea who played a conch shell as though it were a trumpet and he were Louis Armstrong. He wasn’t. Another notable was Ethel the Merman.

Lights! Camera! Gesundheit!

A major motion picture debuted in 1894 and became the first copyrighted film in the United States on January 9. Filmed by the Thomas Edison Studio a few days earlier, it starred a gentleman named Fred Ott. This five-second epic was officially titled “Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze,” but became more familiar as “Fred Ott’s Sneeze.” Next day on Fred Ott’s dressing room, they did not hang a star.