Millard Fillmore ominously assumed the presidency as number 13 when President Zachary Taylor, “Old Rough and Ready,” pushed up presidential daisies in 1850. As the Last of the Red Hot Whigs to hold the office of president, Fillmore had a rather lackluster four years in office before receiving the boot from his own party. He is consistently a cellar dweller in historical POTUS rankings.

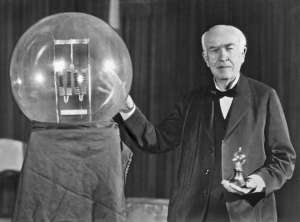

Fillmore’s most lasting legacy, trumpeted in a 1917 article, was the installation of a bathtub, a mahogany model, in the White House, giving the device an imprimatur that paved its way for wider distribution in the United States. This bit of sudsy statesmanship is frequently cited in reference to the Fillmore presidency. The whole story was of course a hoax, fabricated by one of the nation’s less reliable historians, H. L. Mencken. Even though the article was blatantly false and “a tissue of somewhat heavy absurdities,” it was widely quoted as fact for years. “My motive,” Mencken later explained, “was simply to have some harmless fun in war days. It never occurred to me that it would be taken seriously. Soon I began to encounter my preposterous “facts” in the writings of other men…. The chiropractors and other such quacks collared them for use as evidence of the stupidity of medical men. They were cited by medical men as proof of the progress of public hygiene. They got into learned journals and the transactions of learned societies. They were alluded to on the floor of Congress. The editorial writers of the land, borrowing them in toto and without mentioning my begetting of them, began to labor them in their dull, indignant way. They crossed the dreadful wastes of the North Atlantic, and were discussed horribly by English uplifters and German professors. Finally, they got into the standard works of reference, and began to be taught to the young.”

Old Rub-a-Dub-Dub joined Old Rough and Ready on March 8, 1874.

.

For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong. — H. L. Mencken