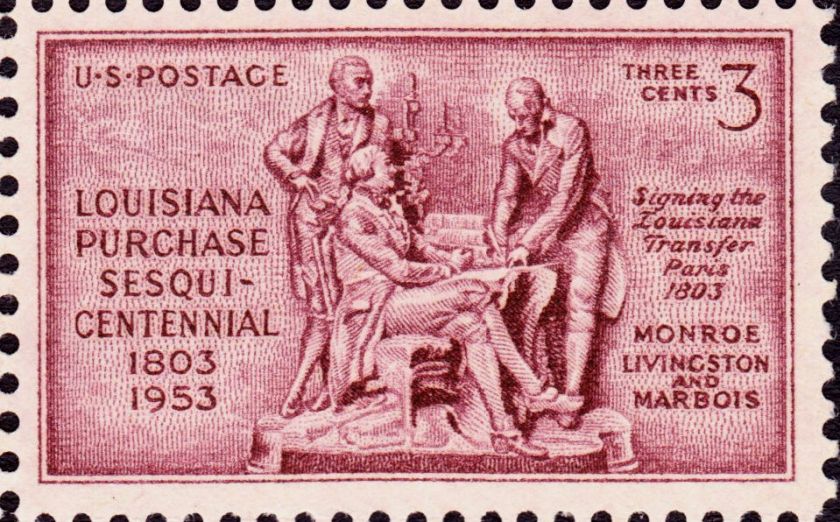

The United States purchased the Louisiana Territory from France in 1803, more than doubling the size of the nation. In addition to the city of New Orleans and western Louisiana, the purchase included  Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska; most of North and South Dakota; parts of Minnesota, New Mexico Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado (portions of Texas were included for ordering before 1804).

Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska; most of North and South Dakota; parts of Minnesota, New Mexico Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado (portions of Texas were included for ordering before 1804).

The price paid was 50 million francs (55 million without Texas). With the Dutch purchase of Manhattan in mind, President Jefferson had hoped to pay for the acquisition using beads. The frontierspeople would have none of it (“We may die without our boots on, but we won’t wear no sissy beads.”) and the people of New Orleans already had so many beads they held a party each year to give them away.

The purchase was pricey compared to the Dutch purchase of Manhattan ($15 million versus $24 in American currency; but since there was no American currency when the Dutch bought Manhattan, the comparison is like comparing guilders and tulips – and guilders and tulips went a lot farther back in 1626). In another comparison, the United States paid 223 million rubles for Alaska. That’s 7.2 million dollars, 32 million francs, 18 million guilders, or 41 million tulips.

And Maybe a Few Brownies

In the 1968 movie I Love You Alice B. Toklas, Peter Sellers places an uptight lawyer who gets lost in the San Francisco counter-culture. Featured prominently in the story is a notorious marijuana-laced brownie first introduced in a book by Alice Babette Toklas, an American writer born on April 30, 1877 in San Francisco.

Shortly after the 1906 earthquake, Toklas moved to Paris where she and her life-long companion, Gertrude Stein, immersed themselves in an earlier counterculture, the Parisian avant-garde of the early 20th century. They hosted a steady parade of American expats including such writers as F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thornton Wilder and Ernest Hemingway.

Toklas’ 1954 book, The Alice B. Toklas Cookbook, was a curious mix of recipes and reminiscences, most notably featuring the recipe for Haschich Fudge, the brownie that became a film star.