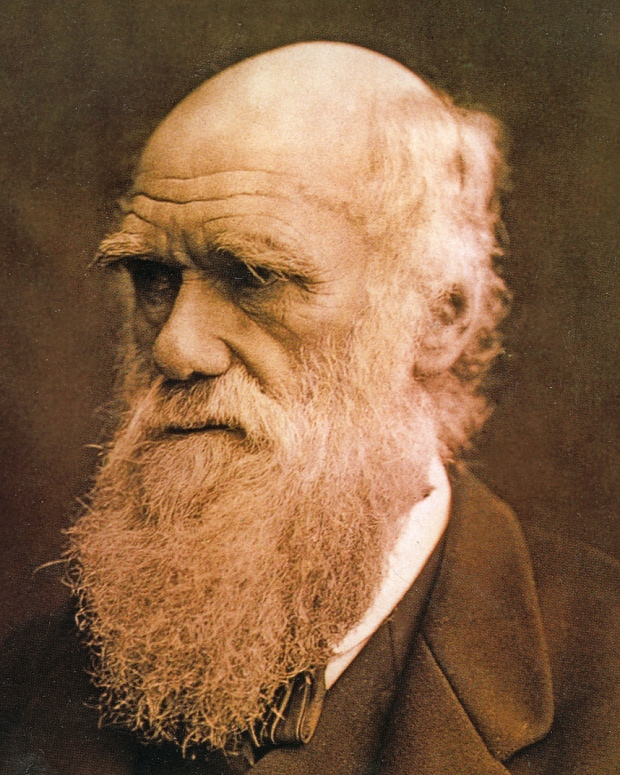

Charles Darwin was not expecting a seismic event when on November 24, 1859, he introduced a little volume with the catchy title On the Origin of Species. Although it didn’t go viral at the time, the printing run of 1,250 copies did sell out. A few more have sold since then.

In his book, Darwin suggested that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestors. That sounds a lot like a plug for family values, but weren’t people upset anyway. Although Darwin’s only allusion to human evolution was a cryptic “light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history,” the title of his book might just as well have been Men from Monkeys because that’s what detractors brought away from it. And any attempt on the part of scientists to explain that it’s not about that pretty much put people to sleep. Even though enlightenment eventually crept into the scientific community, to many others Darwin became forever the symbol of runaway science. Were he alive today, he’d probably be conspiring with the 99 percent of scientists involved in the vast climate change hoax.

In his book, Darwin suggested that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestors. That sounds a lot like a plug for family values, but weren’t people upset anyway. Although Darwin’s only allusion to human evolution was a cryptic “light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history,” the title of his book might just as well have been Men from Monkeys because that’s what detractors brought away from it. And any attempt on the part of scientists to explain that it’s not about that pretty much put people to sleep. Even though enlightenment eventually crept into the scientific community, to many others Darwin became forever the symbol of runaway science. Were he alive today, he’d probably be conspiring with the 99 percent of scientists involved in the vast climate change hoax.

♠

What is Man? Man is a noisome bacillus whom Our Heavenly Father created because he was disappointed in the monkey. ― Mark Twain

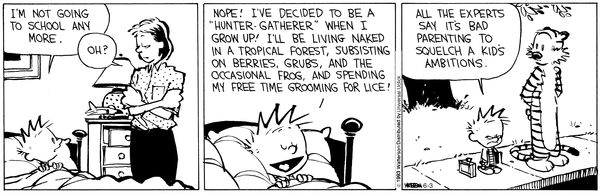

New Rule: Stop asking Miss USA contestants if they believe in evolution. It’s not their field. It’s like asking Stephen Hawking if he believes in hair scrunchies. Here’s what they know about: spray tans, fake boobs and baton twirling. Here’s what they don’t know about: everything else. If I cared about the uninformed opinions of some ditsy beauty queen, I’d join the Tea Party. ― Bill Maher

It is even harder for the average ape to believe that he has descended from man. ― H.L. Mencken

Organic life, we are told, has developed gradually from the protozoan to the philosopher, and this development, we are assured, is indubitably an advance. Unfortunately it is the philosopher, not the protozoan, who gives us this assurance. ― Bertrand Russell