With the usual pomp and circumstance, the marriage and coronation of King George III of England and Charlotte Sophia of Mecklenburg-Strelitz took place on September 22, 1761. The couple were married on the day they met, but remained married for 50 years and 15 children. George was a notable monarch for several reasons, the most familiar being the loss of the American colonies and his supposed madness. Although many people see a link between the two, it’s a stretch. He was also the longest reigning monarch at 60 years until the reign of his granddaughter Queen Victoria.

George didn’t really lose the American colonies any more than George Washington found them. But independence “happened on his watch” a phrase Americans in the future would delight in applying to practically anything gone wrong. Also on his watch, Great Britain defeated the French in the Seven Year’s War and once again many years later the French under Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo.

In his later life, George III had recurrent, and eventually permanent, mental illness. Finally in 1810, a regency was established, and George III’s oldest son, George (coincidentally), ruled as Prince Regent. On III’s death, George Jr. succeeded his father as George IV.

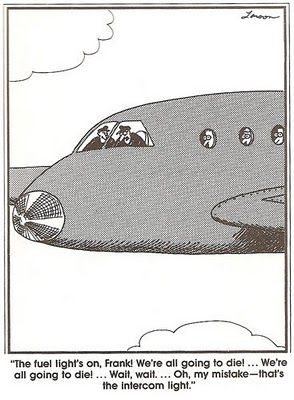

The subject of George III’s mental illness was explored in the play The Madness of George III which inspired the movie The Madness of King George. The name change was supposedly for other reasons, but some maintain that it was because American audiences would think The Madness of George III was a sequel and wonder what happened to the first two movies.

O Mighty Caesar

“He is blessed with a kind of magic truth, the uncanny ability to project the core and humanity of the character he is playing. Beneath the surface humor there is a wry commentary on the conventions and hypocrisies of life.” Sid Caesar was born on September 22, 1922. He lit up 50s television with his incomparable humor on Your Show of Shows and Caesar’s Hour as well as many movies during his long career.