Tagish-Tlingit Packer Keish (Lone Wolf), commonly known as Jim, carried equipment and supplies for early prospectors over the mountain passes from the Alaskan seacoast to the headwaters of the  Yukon River. He earned the nickname “Skookum” (Chinook for big and strong) for his feat of carrying 156 pounds of bacon over Chilkoot Pass in a single trip. (You don’t pull the mask off the old Lone Ranger, And you don’t mess around with Jim.)

Yukon River. He earned the nickname “Skookum” (Chinook for big and strong) for his feat of carrying 156 pounds of bacon over Chilkoot Pass in a single trip. (You don’t pull the mask off the old Lone Ranger, And you don’t mess around with Jim.)

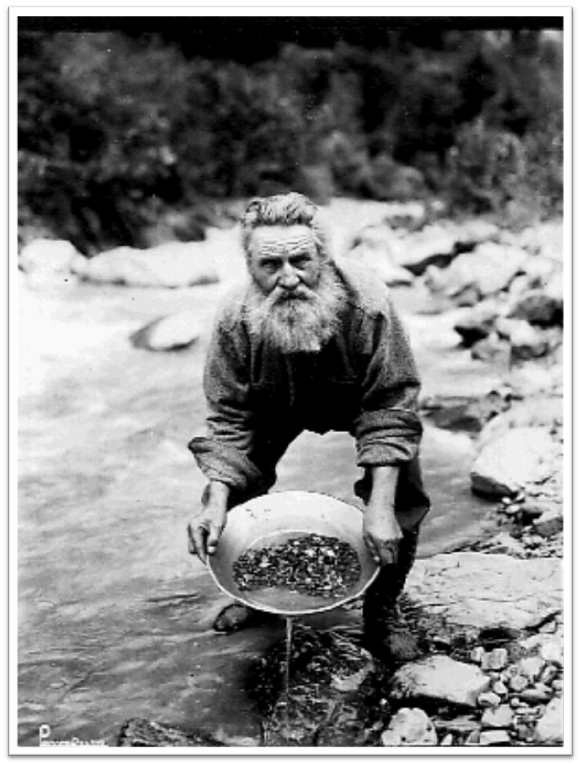

Eventually, tired of slogging other folk’s bacon, Skookum Jim formed a partnership with his sister Shaaw Tlaa (Kate), his cousin Dawson Charlie (Tagish Charlie), and Kate’s husband George Carmack (no nickname) to go look for the Big G.

On August 16, 1896, the Skookum party discovered rich gold deposits in Bonanza (Rabbit) Creek, Yukon. Although Skookum Jim is believed to have made the actual discovery, George Carmack was officially credited for the gold discovery because the actual claim was staked in his name. The group agreed to this because they felt that an Indian’s claim would not be recognized because of the rampant racism of the time.

Well, you can just imagine what happened when word of their discovery got out. The Klondike was suddenly a “destination” for every would-be prospector who ever dreamed of the Big G. The exodus known as the Klondike Gold Rush (Yukon Gold Rush) (Alaskan Gold Rush) (The Gold Rush to End All Gold Rushes) was on.

Together our heroes worked what would become known as Discovery Claim (Look What We Found) and collectively earned nearly a million dollars. Skookum Jim built a home for his wife (the little woman) and daughter (junior) in the Yukon Territory (Tagish First Nation) where he spent the winters trapping, hunting and eating lots of bacon hauled in by others. George and Kate moved to California where he deserted her for another woman. You can’t trust anyone without a nickname.