Not another man swinging through the trees in Africa wearing nothing but a loincloth. Afraid so. Athlete turned actor, Buster Crabbe (born Clarence Linden Crabbe II, on February 7, 1908), followed in Elmo Lincoln’s footsteps, starring as the ape man in Tarzan the Fearless, a 1933 serial that was later compiled into a full-length  movie. Crabbe dived into his movie career after winning Olympic gold for freestyle swimming in 1932.

movie. Crabbe dived into his movie career after winning Olympic gold for freestyle swimming in 1932.

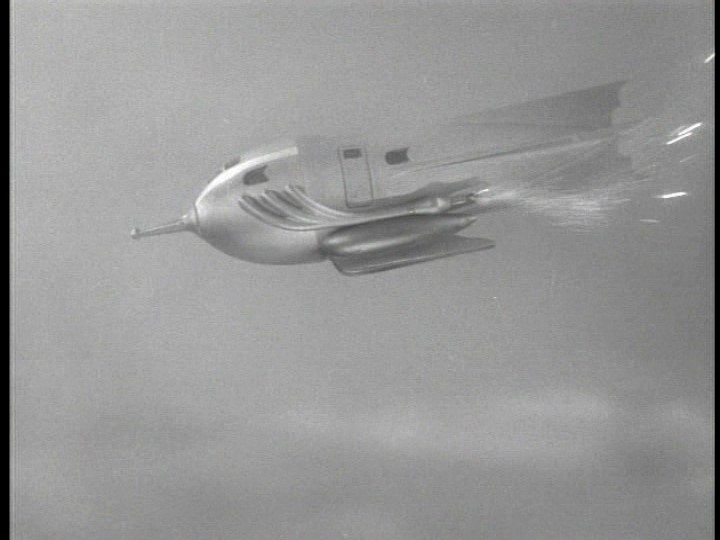

Although he was Tarzan only once, passing his loincloth to Johnny Weissmuller, he played a variety of jungle men in movies such as King of the Jungle, Jungle Man, and King of the Congo. When he wasn’t swinging in the jungle, he was speeding through for the far reaches of space as both Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon, taming the West as Billy the Kid and a posseful of other cowboy heroes, or Americanizing the French Foreign Legion His three Flash Gordon serials were Saturday morning staples in the 30s and 40s. The serials were also compiled into full-length movies. They appeared extensively on American television in the 1950s and 60s, and eventually were edited for release on home video. As his acting career wound down, he became a spokesman for his own line of swimming pools. He died in 1983.

Imagine Jacob Marley in Chains and a Loincloth

Little Charles Dickens knew the adversity he would later write so effectively about. Born February 7, 1812, he attended school in Portsmouth during his early years but was sent to work in a factory in 1824 at the age of 12, when his father was thrown into debtors’ prison. Dickens learned first-hand about the deplorable treatment of working children and the horrors of the institution of the debtors’ prison.

In his late teens, Dickens went to work as a reporter and soon began publishing humorous short stories. A collection of those stories was released in 1836 under the title Sketches by Boz (later titled The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club). The stories about the quixotic innocent Samuel Pickwick and his fellow club members quickly became popular: 400 copies were printed of the first installment, but by the 15th episode the print run had reached 40,000. Publication of the stories in book form in 1837 established Dickens as the preeminent author of his time.

In his late teens, Dickens went to work as a reporter and soon began publishing humorous short stories. A collection of those stories was released in 1836 under the title Sketches by Boz (later titled The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club). The stories about the quixotic innocent Samuel Pickwick and his fellow club members quickly became popular: 400 copies were printed of the first installment, but by the 15th episode the print run had reached 40,000. Publication of the stories in book form in 1837 established Dickens as the preeminent author of his time.

Oliver Twist followed in 1838 and Nicholas Nickleby in 1839. In 1841, Dickens visited the United States, where he was treated as a conquering hero. As a writer, he kept churning out major novels at almost a yearly pace each one seemingly more masterful than the last, among them: David Copperfield in 1850, Bleak House 1853, Hard Times 1854, A Tale of Two Cities 1859 and Great Expectations in 1861.

Dickens was the literary giant of his age, unparalleled in his realism, social criticism and humor, a master of characterization (think Fagin, the Artful Dodger, Pip, Uriah Heep, Oliver Twist, Tiny Tim and, of course, Ebenezer Scrooge). The 1843 novella that featured Scrooge, A Christmas Carol, is one of the most influential works ever written, still popular after 170 years and still inspiring adaptations in every artistic genre. Dickens even has his own adjective, Dickensian.

Dickens died in 1870 at the age of 58, leaving an enigmatic unfinished novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood. He has been celebrated by statuary, in museums and even on currency — all against his dying wishes.

To many generations he will always be the villain he played for the first time in 1936, one of film’s most notable nasties — Ming the Merciless. The evil enemy of the entire universe first appeared in the serial Flash Gordon, battling wits with Buster Crabbe’s Flash. He reprised his role in Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars (1938) and Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe (1940).

To many generations he will always be the villain he played for the first time in 1936, one of film’s most notable nasties — Ming the Merciless. The evil enemy of the entire universe first appeared in the serial Flash Gordon, battling wits with Buster Crabbe’s Flash. He reprised his role in Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars (1938) and Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe (1940). and loved ones have suddenly become emotionless body doubles, all thanks to those strange pods that have been popping up everywhere. Kevin McCarthy has discovered the truth, an alien invasion of human duplicates. Trouble is, no one believes him. As much a horror film as sci-fi, the 1956 Invasion of the Body Snatchers is also a political allegory with most of the scariness in its theme.

and loved ones have suddenly become emotionless body doubles, all thanks to those strange pods that have been popping up everywhere. Kevin McCarthy has discovered the truth, an alien invasion of human duplicates. Trouble is, no one believes him. As much a horror film as sci-fi, the 1956 Invasion of the Body Snatchers is also a political allegory with most of the scariness in its theme.