A certain Miss Molly Mogg of the Rose Tavern in Wokingham, England, turned up her dainty toes on March 7, 1766, at the age of 66. Some 40  years earlier she had been the subject of an amusing ballad written by “two or three men of wit.” The ballad, perhaps to the surprise of its authors, became quite popular. Literary historians have determined that the “men of wit” were Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, and John Gay and that the three were probably quite drunk when they penned the tribute to the pretty Molly.

years earlier she had been the subject of an amusing ballad written by “two or three men of wit.” The ballad, perhaps to the surprise of its authors, became quite popular. Literary historians have determined that the “men of wit” were Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, and John Gay and that the three were probably quite drunk when they penned the tribute to the pretty Molly.

It begins:

The schoolboy delights in a play-day,

The schoolmaster’s delight is to flog;

The milkmaid’s delight is in May-day,

But mine is in sweet Molly Mogg.

and continues on for eleven verses each ending with “sweet Molly Mogg. This, of course required the three rhymesters to come up with 11 words to rhyme with Mogg. Which they did. In addition to the aforementioned flog, there’s bog, cog, frog, clog, jog, fog, dog, log, eclogue and agog — bypassing hog and Prague.

Cogito Airgonaut

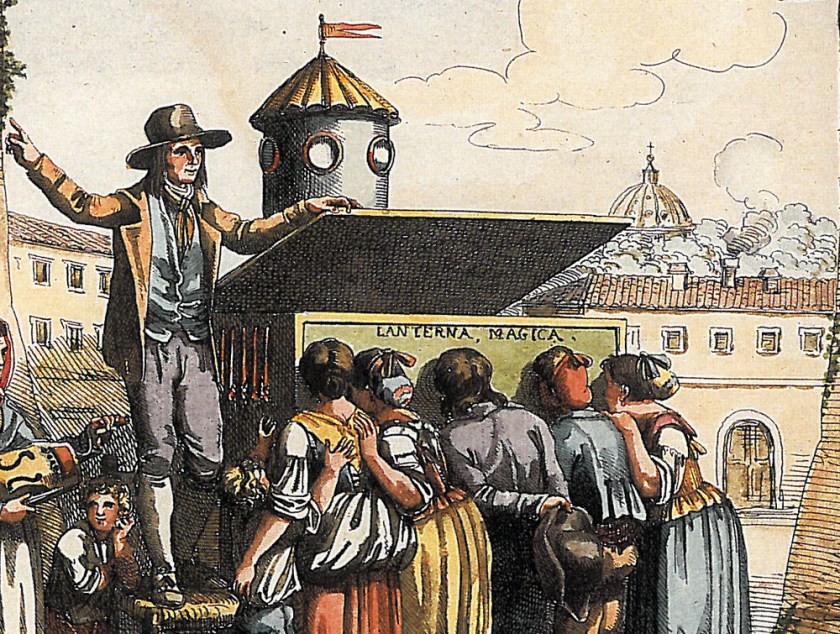

Jean-Pierre Blanchard, the noted 18th century “Airgonaut,” made his first successful balloon flight in Paris back in 1784, in a hydrogen gas balloon launched from the Champ de Mars. Blanchard’s flight nearly ended in disaster, when one spectator slashed at the balloon’s mooring ropes and oars with his sword after being refused a place on board. Observer Horace Walpole wrote of the flight that the Airgonauts were just like birds; they flew through the air, perched in the top of a tree, and some passengers climbed out of their nest to look around.

launched from the Champ de Mars. Blanchard’s flight nearly ended in disaster, when one spectator slashed at the balloon’s mooring ropes and oars with his sword after being refused a place on board. Observer Horace Walpole wrote of the flight that the Airgonauts were just like birds; they flew through the air, perched in the top of a tree, and some passengers climbed out of their nest to look around.

Nevertheless, these early balloon flights set off a public “balloonomania”, with clothing, hairstyles and various objects decorated with images of balloons or styled to resemble a balloon. In 1793, Blanchard scored another first — the first balloon flight in North America, ascending in Philadelphia and landing in New Jersey. Witnesses to the flight included President George Washington, and future presidents John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe. Some say Washington threw a silver dollar at the balloon.

Now famous, our Airgonaut married Marie Madeleine-Sophie Armant in 1804. But his run of fame, fortune and good luck came to a sudden end four years later, when Blanchard had a heart attack while ballooning above the Hague. He fell from his balloon and died of his injuries on March 7, 1809. His widow Sophie inherited everything including the ballooning bug which would be her undoing as well: she continued to support herself with ballooning demonstrations until it also killed her. In 1819, she became the first woman to be killed in an aviation accident when, during an exhibition in the Tivoli Gardens in Paris, she launched fireworks that ignited the gas in her balloon. Her balloon crashed on the roof of a house, and she fell to her death. Don’t try ballooning at home.