They lurk in the watery depths — fearsome creatures beyond imagination created by radioactivity from atomic bomb tests, scientific experimentation, or man’s inhumanity to man. Like the Creature from the Black Lagoon, Orca, or IT Came from beneath the Sea, most of us have only seen them in movies, but we know they’re down there and we know they wish us harm. Now after an October 21, 2011, discovery we can add to the list of terrors keeping us awake at night, Attack of the Giant Xenophyphores.

These guys are way down there — more than 6 miles in the depths of the Mariana Trench. And they weren’t discovered by a couple of drunk fishermen or something. They were discovered by a crack team of scientists from the Scripps Institute of Oceanography in La Jolla, California.

They may not be gigantic in absolute terms, but for single-celled animals — think amoebas — these guys are mammoth at 20 cm. in diameter. There are thousands of them, lying about on the ocean floor, sucking in food from the mud around them, secreting slimy (and most likely deadly) goo all over the place and attaching bits of dead things to themselves (in fact their scientific name means “bearer of foreign bodies”).

Don’t go near the water.

Beware the Frubious Sea-Bishop

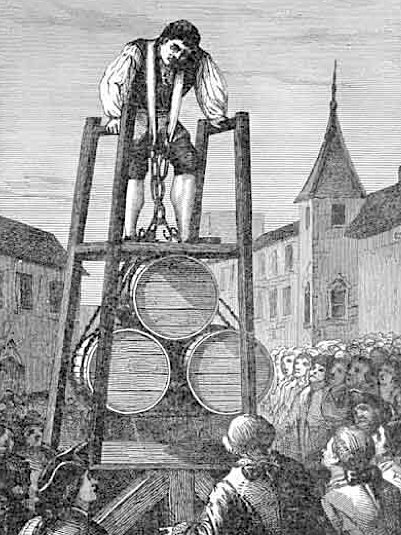

The Elizabethan era was a time of fertile travel, abounding in discoveries that required very little exaggeration to carry them into the realm of the marvelous. And, unlike today, folks would clamor to see anything that was strange, fantastic, beyond belief. This taste for the wonderful was catered to by adventurers returning from voyages with tales of bizarre creatures, monsters even.

Sure, many of the “monsters” would not seem at all unusual today – a shark or an octopus in the possession of a fast-talking charlatan could easily separate country folk from their money. In fact inland people who had never experienced the sea were thought capable of believing just about anything.

Sure, many of the “monsters” would not seem at all unusual today – a shark or an octopus in the possession of a fast-talking charlatan could easily separate country folk from their money. In fact inland people who had never experienced the sea were thought capable of believing just about anything.

Narrations by sixteenth century authors each attempted to outdo each other describing the oddities taken from the sea. One account from 1632, described a creature that, although a fish, bore a striking resemblance to a bishop. And there were drawings to prove its existence. The author pointed out that this was meant to assure us that bishops were not confined to land alone, but that the sea also has the advantage of their blessed presence. This particular sea-bishop was taken before the king and after a conversation expressed his wish to be returned to his own element. The king so ordered and the sea-bishop was cast back into the sea.

No sooner had the creature disappeared than another author in the best tradition of oneupsmanship (and perhaps a bow to evolution) showed us that any sea that possessed a sea-bishop must certainly have a sea-monk!