A lady rode through the streets of London on horseback, naked (the lady not the horse), and didn’t get pinched (in the law and order sense, that is). But more of that later.

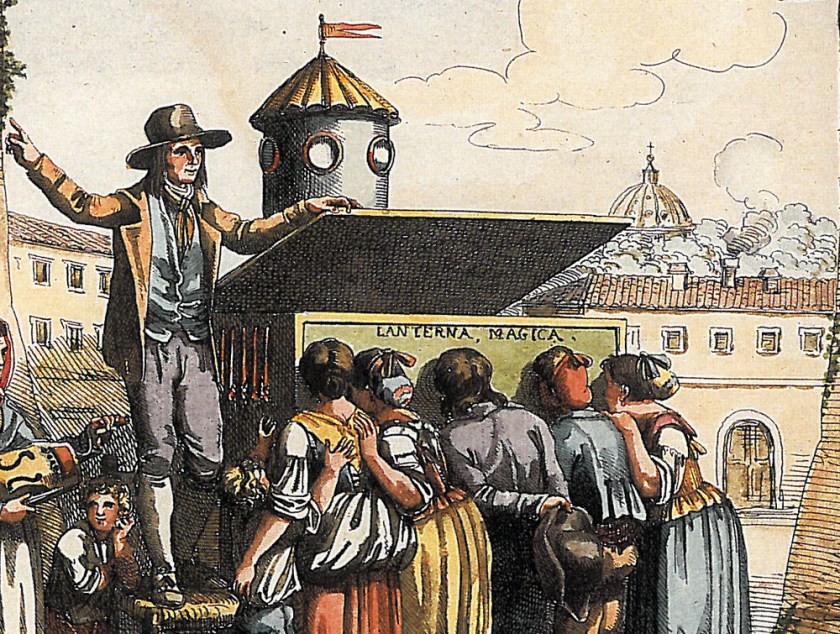

In 1861, Samuel B. Goodale who hailed from Cincinnati received a patent for a clever hand-operated stereoscope device on which still pictures were attached like spokes to an axis which revolved, causing the pictures to come to life in motion — a mechanical peep show that folks viewed through a small hole for a penny a pop. The usual subjects for peep shows were animals, landscapes, and theatrical scenes, high-minded, proper subjects. Nothing naughty or titillating. How long could that last, you ask. Not long of course. The peep show quickly came to stand for pictures and performances involving sex.

The term peep show itself comes from Peeping Tom, a sneaky British tailor who made a hole in the shutters of his shop so he might surreptitiously spy on Lady Godiva who felt the need to ride naked naked through the streets of the city. He was struck blind for his effort.

What about this Lady Godiva? Was she for real? Yes kids, she was. And the performance she is famous for took place back in the 11th century. According to her press agent, Lady Godiva was not just your ordinary exhibitionist giving the folks of Coventry, particularly the Toms, Dicks and Harrys of Coventry, their daily eyeful. She was a noblewoman, married to the “Grim” Earl of Mercia, a nasty fellow who burdened the folks under his sway with high taxes and poor service. Lady Godiva pleaded frequently with her husband to give the poor some relief, to no avail. He eventually agreed to lower the taxes if she would ride through town completely naked. The Lady called his bluff. To keep her ride from becoming something of the magnitude of a Taylor Swift concert, the townspeople were told to shutter themselves indoors with no peeping. Which they did, except for you know who. In a later interview, Blind Tom said it was worth it.

That Ain’t No Cat in the Hat

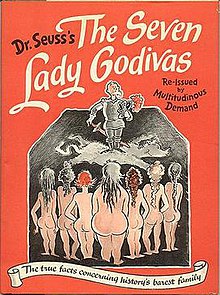

“It was all full of naked women, and I can’t draw convincing naked women. I put their knees in the wrong places.” What’s better than a Lady Godiva? Two Lady Godivas. Or how about seven? The story of the seven Godiva sisters was penned by none other than Dr. Seuss, his fourth book and one written for adults or “obsolete children” as he called them. The seven sisters never wear clothing, not even when they leave the seven Peeping brothers, and head off in the world to warn of the dangers of horses.

“It was all full of naked women, and I can’t draw convincing naked women. I put their knees in the wrong places.” What’s better than a Lady Godiva? Two Lady Godivas. Or how about seven? The story of the seven Godiva sisters was penned by none other than Dr. Seuss, his fourth book and one written for adults or “obsolete children” as he called them. The seven sisters never wear clothing, not even when they leave the seven Peeping brothers, and head off in the world to warn of the dangers of horses.

The 1939 book had a 10,000 print run with most of them remaining unsold, what Seuss called his greatest failure. It is one of only two Dr. Seuss books allowed to go out of print.

But Please Lose That Sports Jacket

It has been endlessly debated when and with whom rock and roll actually began, but most enthusiasts have pretty much settled on a guy who cut an unlikely figure for a rock artist but who brought rock and roll into the public eye with a bang in 1955. The man was Bill Haley, along with his Comets, and the song was “Rock Around the Clock” introduced in the film Blackboard Jungle. During the next few years a string of hits including “Shake, Rattle and Roll” and “See Ya Later, Alligator” followed.

Time passes quickly and when you’re at the pinnacle of musical stardom, you’re on a slippery slope. Along comes a guy named Elvis and you’re yesterday’s sha-na-na. Who’s going to scream and carry on for a thin-haired, paunchy 30-year-old musician with a si lly curl in the middle of his forehead and a garish plaid sports jacket?

lly curl in the middle of his forehead and a garish plaid sports jacket?

The Brits, that’s who.

By 1957, Bill Haley and the Comets had already enjoyed their golden days of American super-stardom. But the battle of Britain lay ahead. When they stepped off the Queen Elizabeth in Southampton on February 5, they began the first ever tour by an American rock and roll act and launched what rock historians called the American Invasion.

When Haley and the band reached London later that same day, they were greeted by thousands in a melee the press called “the Second Battle of Waterloo.” These were the British war babies just becoming teenagers, and they were ready for American rock and roll.