Even in 1411, the people of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon had been making cheese as long as anyone could remember. And all because a young man was lured away from his lunch by a fair young maiden. Or so the story goes.

The cheese-making folks of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon were probably the only ones making the tangy, crumbly sheep’s milk cheese with its distinctive veins of green mold. Nevertheless on June 4, 1411, French King Charles VI granted them a monopoly for the ripening of the Roquefort cheese.

The cheese-making folks of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon were probably the only ones making the tangy, crumbly sheep’s milk cheese with its distinctive veins of green mold. Nevertheless on June 4, 1411, French King Charles VI granted them a monopoly for the ripening of the Roquefort cheese.

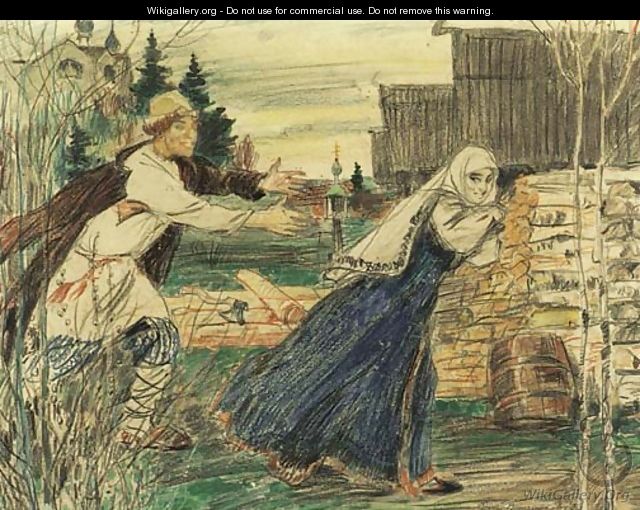

What makes Roquefort Roquefort is its aging in the Combalou caves of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon. Popular legend suggests that the cheese was discovered when a young man eating his lunch of bread and ewe’s milk cheese spied a hot young woman in the distance. Naturally, he ran off to pursue her, leaving his lunch in the cave. Legend leaves the results of his amorous pursuit to our imaginations, but his appetite must have been somehow satisfied since he didn’t return to the cave for several months. When he did, the mold present in the cave – Penicillium roqueforti to be exact – had done an ugly duckling number on his lump of cheese transforming it into a cheese of beauty. The bread, however, was another story.

The French take their wine and their cheese seriously. A ruling in 1961 decreed that although the Roquefort-sur-Soulzon method for the manufacture of the cheese could be followed across the south of France, only those cheeses ripened in the natural caves of Mont Combalou could bear the name Roquefort. Today, its production involves some 4,500 people who herd special ewes on 2,100 farms in a carefully defined grazing area. In 2008, 19,000 tons were produced, with 80% of it consumed in France. It’s a laborious process — 4,500 folk dropping their 4,500 lumps of ewe’s milk cheese and running off in hot amorous pursuit of 4,500 other folk.