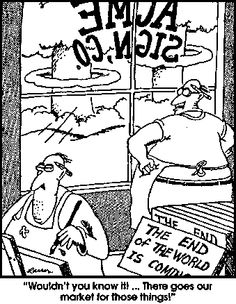

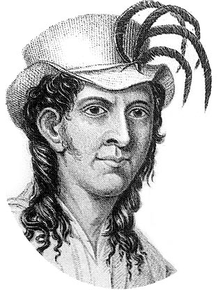

Those who predict the imminent end of the world display a certain amount of chutzpah if not foolhardiness (such as Micheal Stifel, October 19 and William Miller, October 22). It probably takes even more of those qualities to identify the exact date of the beginning of the world, but didn’t James Ussher (1581-1656) do just that.

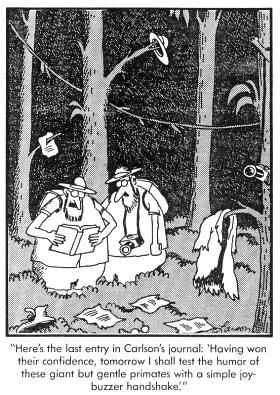

As Archbishop of Armagh, Primate of All Ireland, and Vice-Chancellor of Trinity College in Dublin, Ussher was rather highly regarded in his day as both churchman and scholar. He was not your average man on the street (“Tell me sir, when did the world begin?”) making bold proclamations. And evidently he didn’t just pull important dates out of a hat. His declarations were based on an intricate correlation of Middle Eastern and Mediterranean histories and Holy writ, incorporated into an authorized 1701 version of the Bible, or so he explained. And they were accepted, regarded without question as if they were the Bible itself.

Through the aforementioned methods, Ussher established that the first day of creation was Sunday, October 23, 4004 BC. He didn’t give a time. On a roll, Ussher calculated the dates of other biblical events, concluding, for example, that Adam and Eve were driven from Paradise on Monday, November 10 of that same year BC. (It took them less than three weeks to get in trouble with God.) And Noah docked his ark on Mt Ararat on May 5, 2348 BC. That was a Wednesday if you were wondering.

Late-breaking news: Dr. John Lightfoot, of Cambridge, an Ussher contemporary, declared in a bold bid for oneupsmanship, that his most profound and exhaustive study of the Scriptures, showed that “heaven and earth, centre and circumference, were created all together, in the same instant, and clouds full of water,” and that “this work took place and man was created by the Trinity on October 23, 4004 B.C., at nine o’clock in the morning.”

Okay Lightfoot, Take This

Wretched Richard will jump out onto the proverbial limb and give you a few more dates you might be wondering about.

January 29, 3995 BC, 8 a.m. — God creates children.

March 12, 3906 BC, 5:00 p.m. — Shouting something about his damn sheep, Cain slays Abel.

September 3, 3522 BC, 6:00 p.m. — God creates Facebook, then decides the world isn’t ready for it.

October 2, 2901 BC, 4:00 p.m. God, having been in a bad mood all day, turns Lot’s wife into a pillar of salt.

June 7, 2549 BC 11:15 a.m. God once again in a creative mood creates marijuana.

1:30 p.m. –Later that day, God, thoroughly annoyed with all his creations except his latest, instructs Noah to build an ark because he, God, is going to destroy the world.

August 14, 2371 BC, 5:30 a.m. — Methuselah finally turns his toes up after 969 years on this good earth.

July 7, 1425 BC, 8:30 p.m. — God gives Moses the Ten Commandments.

March 1, 2 AD, 10:15 a.m. — God creates an amusing diversion featuring Christians and lions.

July 2, 1854 AD, 11:45 p.m. — After a few too many martinis, God creates Republicans.

November 9, 2016, 2:45 a.m. — Feeling rather wicked, God makes Donald Trump president.

November 5, 2024, 10 a.m. — A big grin spreads across God’s face . . .