Russian dancer and actress Ida Rubenstein convinced her friend Maurice Ravel to write her a Spanish flavored ballet in 1928. The composer had long considered the idea of structuring an entire composition around a single theme. The theme came to him on a vacation a few month’s later. He sat at a piano playing a melody with one finger. As he played, he said to a friend: ‘Don’t you think that has an insistent quality? I’m going to try to repeat it a number of times without any development, gradually increasing the orchestra as best I can.”

Bolero was born. It was performed on November 22, 1928, at the Paris Opera. The 15-minute work was received with thunderous acclaim — cheering, shouting, foot stomping. One woman was heard screaming “Au fou, au fou!” (the madman, the madman). Ravel’s reaction, when told of it: “That lady, she understood.”

Rarely staged as a ballet in later years, Bolero became Ravel’s most popular work, although he considered it one of his least important. “Once the idea of using only one theme was discovered,” he said, “any conservatory student could have done as well.”

Time Flies Like an Arrow

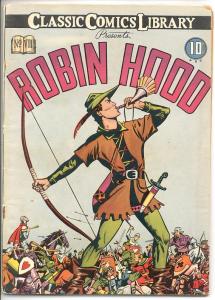

Robin Hood has been celebrated through story, song and film as that charming rogue who, along with his merry men, robbed from the 1 percent and gave to the 99 percent, a nobleman cheated out of his birthright by the nasty Sheriff of Nottingham, a patriot in service to Richard the Lionhearted, fighting the villainy of that usurper Prince John.

the Lionhearted, fighting the villainy of that usurper Prince John.

To the consternation of the authorities, Robin Hood and his merry gang carried out their trade for a number of years. But as Robin Hood ushered in his 87th year, his arrows began to get a little wobbly and off-target. He increasingly felt the infirmities of his age, and was eventually convinced to seek medical attention at the local nunnery. The prioress evidently took an instant dislike to the merry old man, which she vented by opening up an artery and allowing him to bleed to death. The date of his demise is reckoned to be November 22, 1247.

But before he turned his toes completely up, Robin realized that he was the victim of treachery (flowing blood will do that), and he blew a blast on his bugle (kept handily at his bedside for just such a situation). This summoned his compatriot Little John who forced his way into the chamber in time to hear his chief’s last request. “Give me my bent bow in my hand,” he said. “And an arrow I’ll let free, and where that arrow is taken up, there let my grave digged be.” Rhyming right to the end. Which came just after he shot the arrow through an open window, selecting the spot where he should be buried. Which he was.