On November 5, 1975, Travis Walton and a half dozen co-workers had finished up their day’s work in the Apache-Sitgreaves National forest near Snowflake, Arizona. As they departed the forest in a pickup truck, they found themselves facing a huge hovering subject blocking the road a hundred feet ahead of them and making an unfriendly buzzing sound. It was of course saucer-shaped.

Travis, evidently the bravest of the bunch, jumped out of the truck and approached the saucer. It is unclear whether he planned to welcome it to Earth, say take me to your leader or tell them to get the hell out of the way before he called in the army with its grenade launchers, bazookas and itchy trigger fingers. It really didn’t matter because before he could say anything that saucer up and zapped him with a nasty beam of light that knocked him unconscious.

Naturally his coworkers ran to his aid. Not really. Actually, they turned that truck around and sped off.

Travis was missing for five days. During those five days, he says, he awoke in what appeared to be a hospital being poked and prodded by three creatures that looked a lot like Dopey of the Seven Dwarfs. They were little, so Travis attempted to beat them up, but was himself subdued by a big guy in a helmet. The big guy and several cohorts forced a plastic mask over Travis’ face and he once again passed out. He awoke on a lonely stretch of highway with the saucer speeding off into the twilight.

Travis was missing for five days. During those five days, he says, he awoke in what appeared to be a hospital being poked and prodded by three creatures that looked a lot like Dopey of the Seven Dwarfs. They were little, so Travis attempted to beat them up, but was himself subdued by a big guy in a helmet. The big guy and several cohorts forced a plastic mask over Travis’ face and he once again passed out. He awoke on a lonely stretch of highway with the saucer speeding off into the twilight.

Fortunately for Travis, a $5,000 National Enquirer prize for the best true account of an alien abduction took some of the sting out of his unpleasant experience.

Please To Remember, the Fifth of November

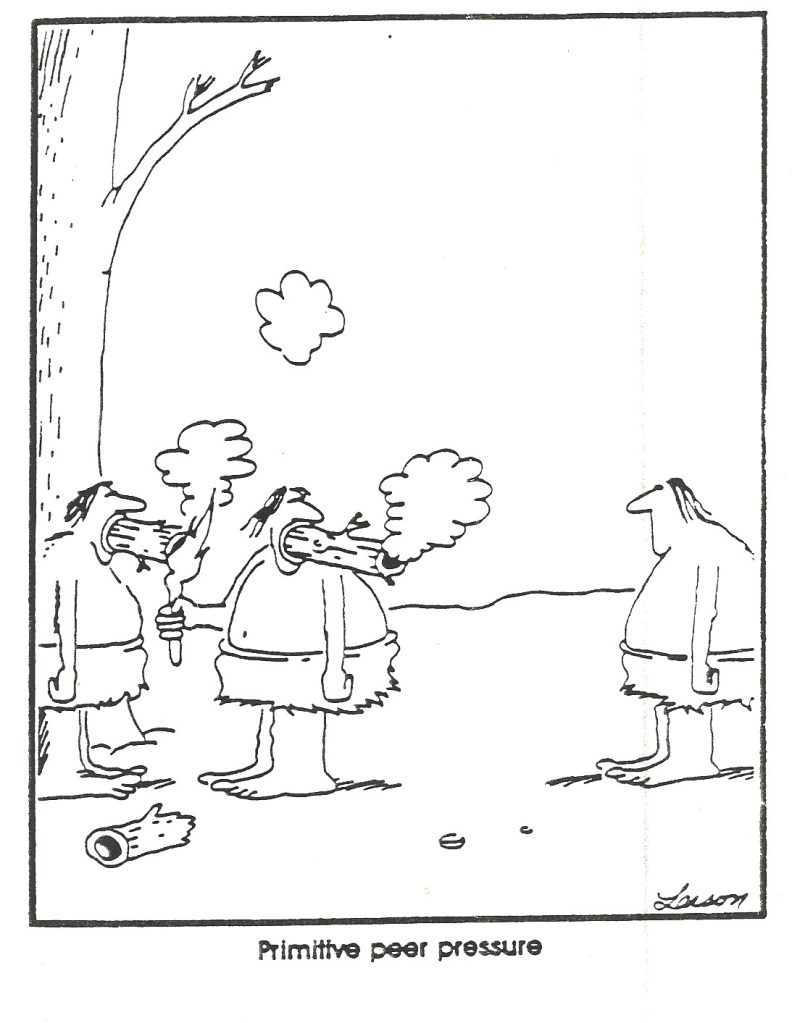

As if the juvenile delinquents of the world couldn’t get in enough trouble on Halloween, they get another opportunity to misbehave, at least in England, on Guy Fawkes Day. On this day, November 5, it has long been customary to dress up a scarecrow figure and, sitting it in a chair, parade it through the streets. Those unlucky enough to be passers by are solicited for cash contributions with shouts of “Pray remember Guy” which the passers by hear as “Your money or your life.” Once the revelers have extorted enough money, they built a big bonfire and merrily burn their scarecrow, pretending it is Guy Fawkes or the Pope or the Prime Minister or their history teacher.

Who Is Guy Fawkes, You Ask

Guy Fawkes was a protester some four hundred years ago, a member of a group of English Catholics who were dismayed at having a Protestant as King of England. Their protests eventually moved beyond the verbal assaults (“Hi de hay, hi de ho, King James the First has got to go”) down the slippery slope to gunpowder, treason and plot.

Guy Fawkes was a protester some four hundred years ago, a member of a group of English Catholics who were dismayed at having a Protestant as King of England. Their protests eventually moved beyond the verbal assaults (“Hi de hay, hi de ho, King James the First has got to go”) down the slippery slope to gunpowder, treason and plot.

Guy Fawkes was born in England in 1570 but as a young man went off to Europe to fight in the Eighty Years’ War (not the entire war, of course) on the side of Catholic Spain. He hoped that in return Spain would back his Occupy the Throne movement in England. Spain wasn’t interested.

Guy returned to England and fell in with some fellow travelers. Realizing that the Occupy the Throne movement required removing the person who was currently sitting on it, the group plotted to assassinate him. They rented a spacious undercroft beneath Westminster Palace where they amassed a good supply of gunpowder. Guy Fawkes was left in charge of the gunpowder.

Unfortunately, someone snitched on them and Fawkes was captured on November 5. Subjected to waterboarding and other enhanced interrogation methods, Fawkes told all and was condemned to death. (Evidently, James I was not amused.) Just before his scheduled execution, Fawkes jumped from the scaffold, breaking his neck and cheating the English out of a good hanging.

Since then the English have celebrated the failure of the Gunpowder Plot in 1605 with the November 5 celebration, an integral part of which is burning Guy Fawkes (and sometimes others) in effigy. Seems like a long time to hold a grudge.