November 25 marks the feast of St. Catherine of Alexandria who was born in 287. As a young teenager, Catherine was evidently pretty, witty and wise. Devoting herself to an uncharacteristic amount of study for a teenager, she found herself lured into the ways of Christianity, which was not a particularly popular pursuit at the turn of the 4th century. In fact, the evil emperor Maxentius was quite put out by her piety, particularly when she called him on his cruelty, right to his face.

Not only that, he was obsessed enough with her religiosity that he summoned fifty noted pagan philosophers to convince her that her religion was a passing fad. But didn’t she whup them good in all their debates. In fact, she argued her case so eloquently that many of them converted. They were of course immediately put to death.

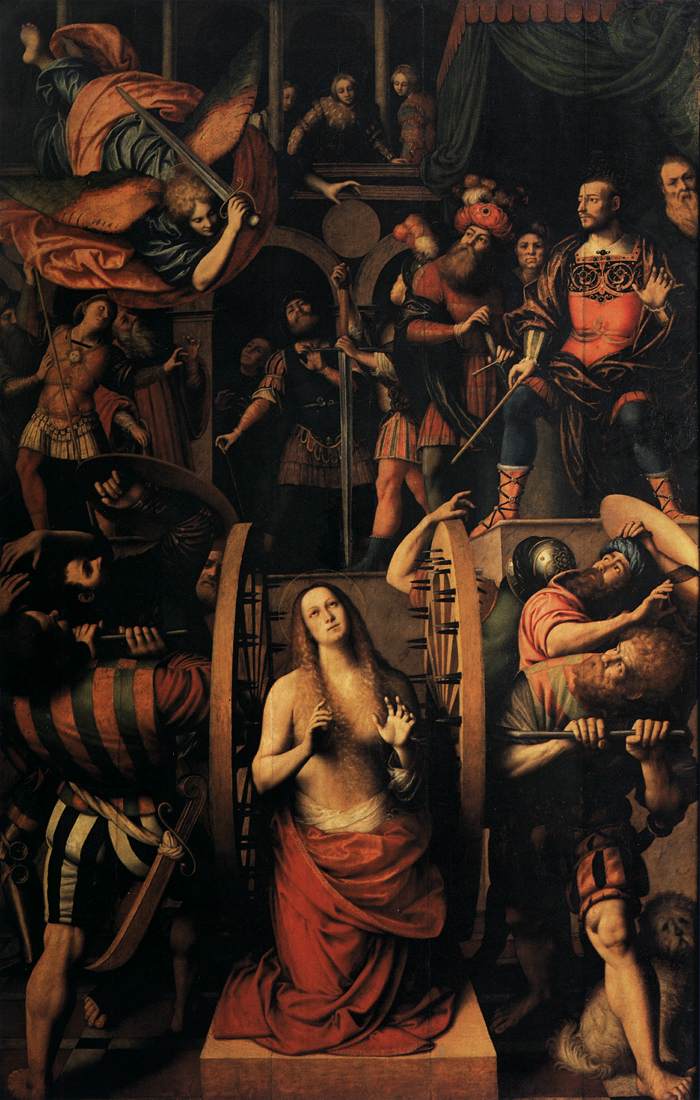

Maxentius then had Catherine thrown into prison, where she continued to convert those who came to visit her. He had her tortured, and when that yielded no results, he took the next logical step and asked her to marry him. She refused, giving him the excuse that she wanted to remain a virgin and telling him they could remain friends (if he’d give up the cruelty). This really annoyed him so he condemned her to death on a spiked breaking wheel. When she touched the wheel, however, it shattered, a bit of a miracle for which she would always be remembered by the nickname St. Catherine of the Wheel. Unfortunately, she was beheaded shortly thereafter (at least never being given the sobriquet St. Catherine the Headless).

As a dead virgin, a martyr, and then a saint, her popularity grew steadily, and she was eventually named one of the fourteen most helpful saints in heaven. As such, she is the patron saint to all sorts of people — potters and spinners (think wheel), unmarried girls and/or virgins, mechanics, knife sharpeners, librarians, milliners and philosophers to name just a few. The latter sought her help to sharpen their minds, guide their pens, and bring eloquence to their words.

Obviously, Wretched Richard’s Almanac got no such help.