In 1989, the United States Post Office issued a series of four stamps depicting dinosaurs, little realizing that it was re-igniting the infamous Bone Wars of more than a hundred years earlier.

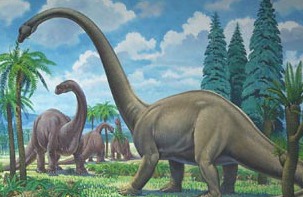

The Bone Wars, also known as the Great Dinosaur Rush, was a period of fossil fever during the late 19th century during which a heated rivalry between two paleontologists (yes, it sounds bizarre) led to dirty tricks, bribery, theft, and even the destruction of bones. Each scientist also attacked the other in scientific print, hoping to ruin his credibility and have his funding cut off. During this period, one of the combatants hastily brought to public that big cuddly dinosaur we’ve come to love, the brontosaurus. Turns out he had gone public with that same dinosaur a couple of years earlier under an entirely different name, apatosaurus.

Another paleontologist brought this mistake to light in 1903, pointing out that protocol required the first name used, apatosaurus, to be the official name. Why did the name continue to be used in popular books, articles and even on museum displays? It seems the 1903 discovery was only presented in a very obscure scientific journal. It took another 70 years for the brontosaurus to officially get the boot to synonym status.

And along comes the U.S. Post Office in 1989 identifying the big guy as a brontosaurus. Well, didn’t some dinosaur groupies with not enough to keep themselves busy get all hot and bothered, accusing the Postal Service of promoting scientific illiteracy. And even after this brouhaha, most of us still insist on having our brontosaurus.

Maybe it’s because brontosaurus means “thunder lizard” and apatosaurus means (ho-hum) “deceptive lizard.”

You Thought These Guys Were Big?

Compared to Bronto or Apato or practically any other dinosaur you’d like to name, we homo sapiens are a rather puny lot these days, even those few who top out at seven feet or so. Back in the day, as they say — way back in the day — folks were somewhat larger. We have a very convenient  catalog of how we don’t measure up provided for us back in 1718 by an astute French academician named Henrion. Both his first name and biography have been lost to the ages (he was probably short). What remains, however, is his scholarly demonstration of the height of several important figures.

catalog of how we don’t measure up provided for us back in 1718 by an astute French academician named Henrion. Both his first name and biography have been lost to the ages (he was probably short). What remains, however, is his scholarly demonstration of the height of several important figures.

Starting right at the beginning as Henrion did, Adam was a towering drink of water at 123 feet, 9 inches. Interestingly he had been even taller. When first created, he was so tall his head reached into the heavens where it evidently nonplussed the angels enough that God was forced to shrink him to a more comfortable size. God very wisely kept him taller that Eve’s 118 feet, 9 inches. (Adam would have looked pretty silly with a fig leaf and elevator shoes.)

The kids didn’t measure up to their parents, nor did the next generation. In fact, a significant downsizing was underway. Noah was only 27 feet tall, Abraham 20 feet, and Moses a mere 13 feet. (The trend is becoming alarming!) Alexander was hardly the Great at six feet, and Julius Caesar was downright little at five feet. Mankind was on a course that would leave us microscopic little things, not even visible to the naked eye.

But, according to the learned Monsieur Henrion, Christianity saved us. We got religion and began to grow again.

To many generations he will always be the villain he played for the first time in 1936, one of film’s most notable nasties — Ming the Merciless. The evil enemy of the entire universe first appeared in the serial Flash Gordon, battling wits with Buster Crabbe’s Flash. He reprised his role in Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars (1938) and Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe (1940).

To many generations he will always be the villain he played for the first time in 1936, one of film’s most notable nasties — Ming the Merciless. The evil enemy of the entire universe first appeared in the serial Flash Gordon, battling wits with Buster Crabbe’s Flash. He reprised his role in Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars (1938) and Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe (1940). and loved ones have suddenly become emotionless body doubles, all thanks to those strange pods that have been popping up everywhere. Kevin McCarthy has discovered the truth, an alien invasion of human duplicates. Trouble is, no one believes him. As much a horror film as sci-fi, the 1956 Invasion of the Body Snatchers is also a political allegory with most of the scariness in its theme.

and loved ones have suddenly become emotionless body doubles, all thanks to those strange pods that have been popping up everywhere. Kevin McCarthy has discovered the truth, an alien invasion of human duplicates. Trouble is, no one believes him. As much a horror film as sci-fi, the 1956 Invasion of the Body Snatchers is also a political allegory with most of the scariness in its theme.