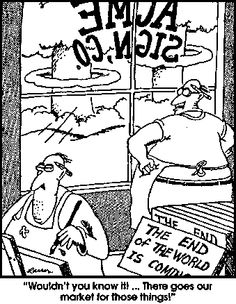

One would think they’d learn a lesson from the many prognosticators who predicted the end of the world only to end up with egg on their faces. But no, there seems to be an endless queue of folks wanting to give it a go. William Miller might well be the most famous (or infamous) of these Jeremiahs. He reached the front of the line in the 1840s.

Miller preached his doomsday story to a large group of followers known, strangely enough, as Millerites. At least Miller didn’t get as specific as many others who predicted the exact date and time of the finale. Miller hedged his bets a bit, calling for the long-awaited Second Coming and the great big beautiful bonfire to take place sometime between March of 1843 and March of 1844. He publicized the event with posters, speeches, pamphlets and tweets (no, strike that last one). As a result, he convinced 100,000 true believers to unload all their stuff and head up to the mountains to usher in the Apocalypse.

Well, they waited. And waited. 1843 became 1844. March came in like a lion and went out like a lamb. Miller recalculated and set a new date for the final comeuppance: April 18. April showers brought May flowers, but not much else. Did our plucky prophet of doom fold up his tent? No way. Another recalculation, another date. October 22, and you can take that to the bank. The Millerites, who by this time should have been used to having their expectations dashed, went once more to the mountains.

Well, they waited. And waited. 1843 became 1844. March came in like a lion and went out like a lamb. Miller recalculated and set a new date for the final comeuppance: April 18. April showers brought May flowers, but not much else. Did our plucky prophet of doom fold up his tent? No way. Another recalculation, another date. October 22, and you can take that to the bank. The Millerites, who by this time should have been used to having their expectations dashed, went once more to the mountains.

October 22, 1844: Oh somewhere in this favored land, the sun is shining bright, the band is playing somewhere, and somewhere hearts are light, and somewhere men are laughing, and somewhere children shout; but there is no joy on the mountain — William Miller has struck out.

In some religious circles, October 22, 1844, is known as the Great Disappointment.